Forty-four men, women and children were robbed, beaten and abused before being set adrift on the open sea in the latest outrage carried out by uniformed Greek operatives.

And the ‘crime’ committed by these 44 people, to justify their horrifying experience at the hands of people who are paid to save and safeguard human lives? Nothing at all. They were simply attempting to find a safe place to live, learn and work.

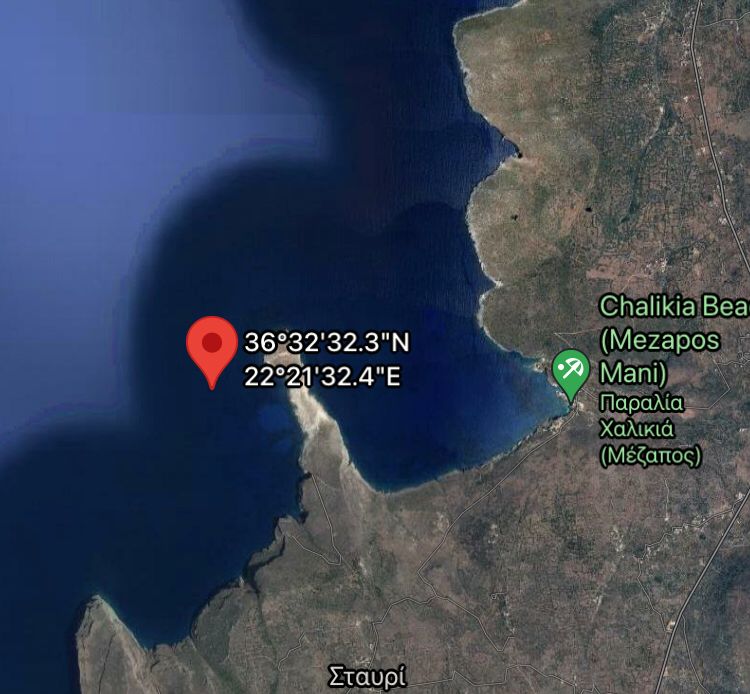

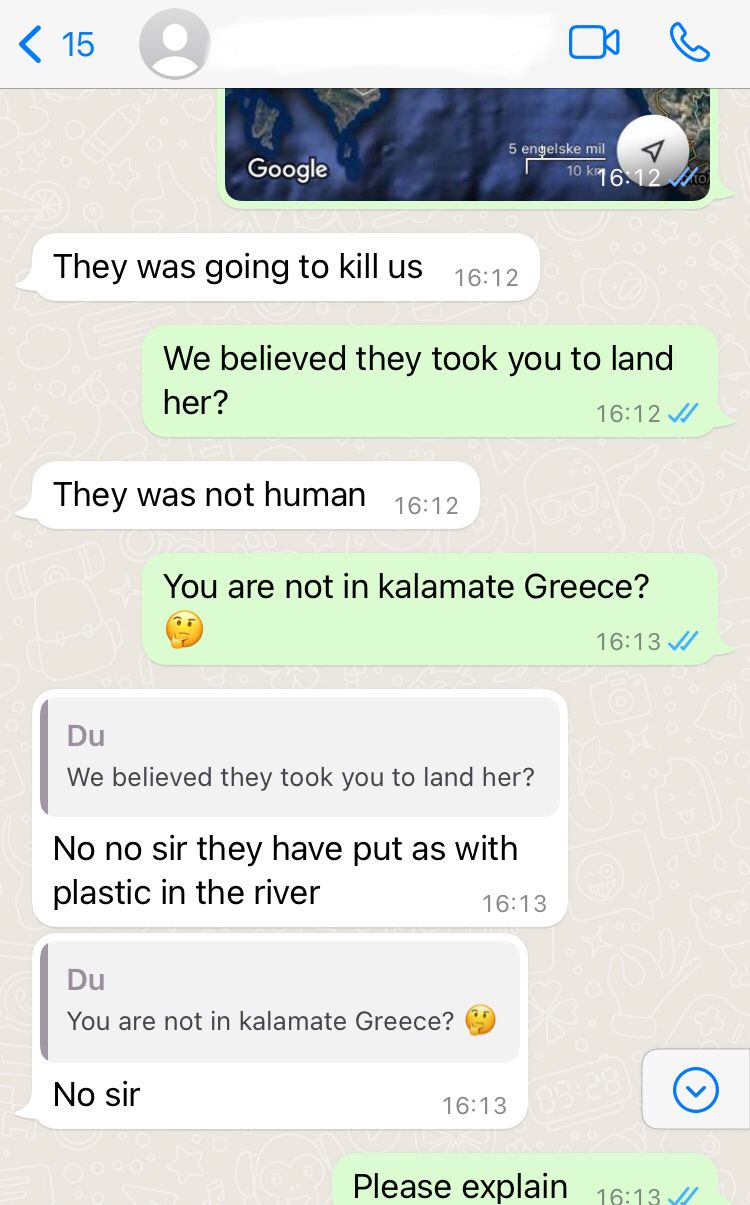

At 11.48pm (EET) on 14 November, 44 people on a sailboat in distress, north west of Stavri, Peloponnese, contacted Aegean Boat Report.

The smuggler who had sailed the boat from Turkey towards Italy had abandoned them after the boat’s engine malfunctioned, leaving them drifting helplessly dangerously close to the cliffs in the area.

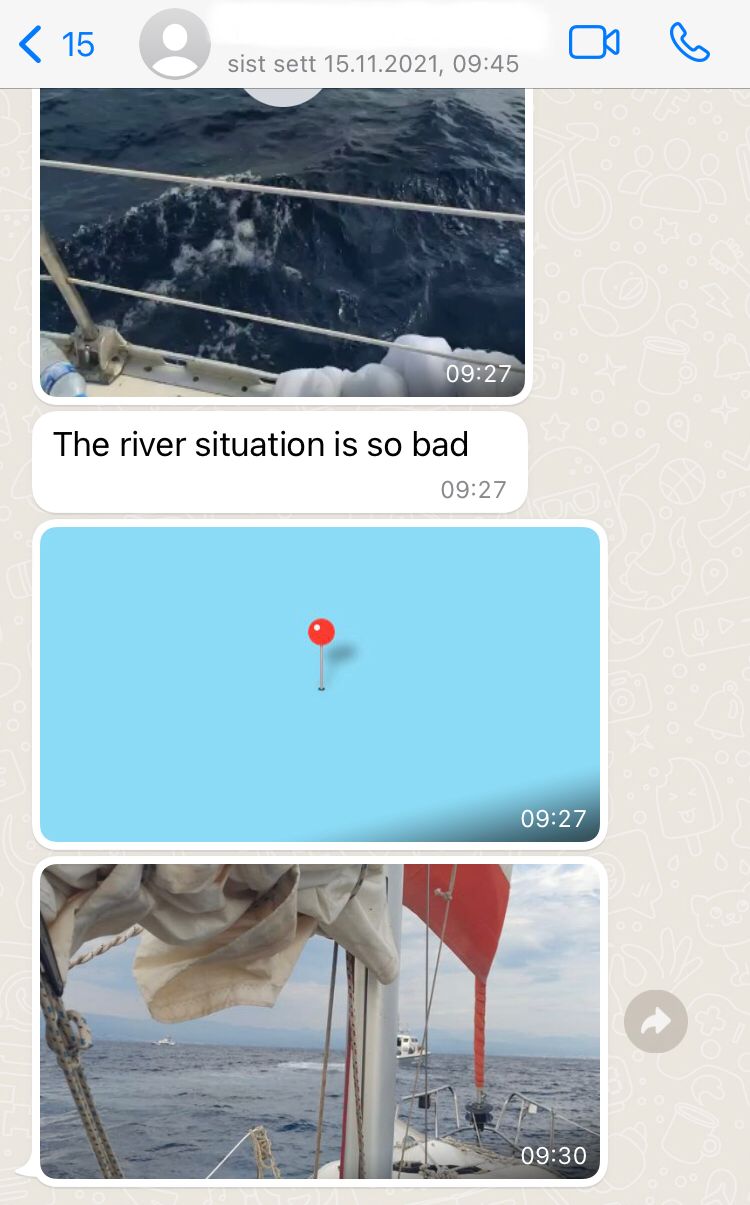

The weather was rough: heavy wind and waves were pushing the boat towards land. The situation was critical.

Aegean Boat Report told the passengers to contact emergency services on 112 immediately, and at the same time we called the Ministry of Shipping & Island Policy in Piraeus.

The call was immediately rerouted to the emergency call centre of the Hellenic coast guard.

Usually, a distress call to any emergency service in Europe doesn’t take more than a minute: information is provided, some questions are asked about who is calling, the location, situation etc., and help is on its way.

When calling the Hellenic coast guard on cases involving refugees in distress, however, the situation is quite different.

They are normally more interested in who you are and how you know something is happening, than in the emergency you are trying to help with, wasting precious time when you have none to spare.

It took me 10 minutes to make this call, and most of the questions the operator asked were about me, not the emergency I was desperately trying to get help for.

In many calls I have made over the years to the Hellenic coast guard to alert them about emergencies at sea, it’s not only the time waisted in pointless interrogations that is frustrating: in many cases SAR operations are deliberately delayed for hours, and people drown as a result.

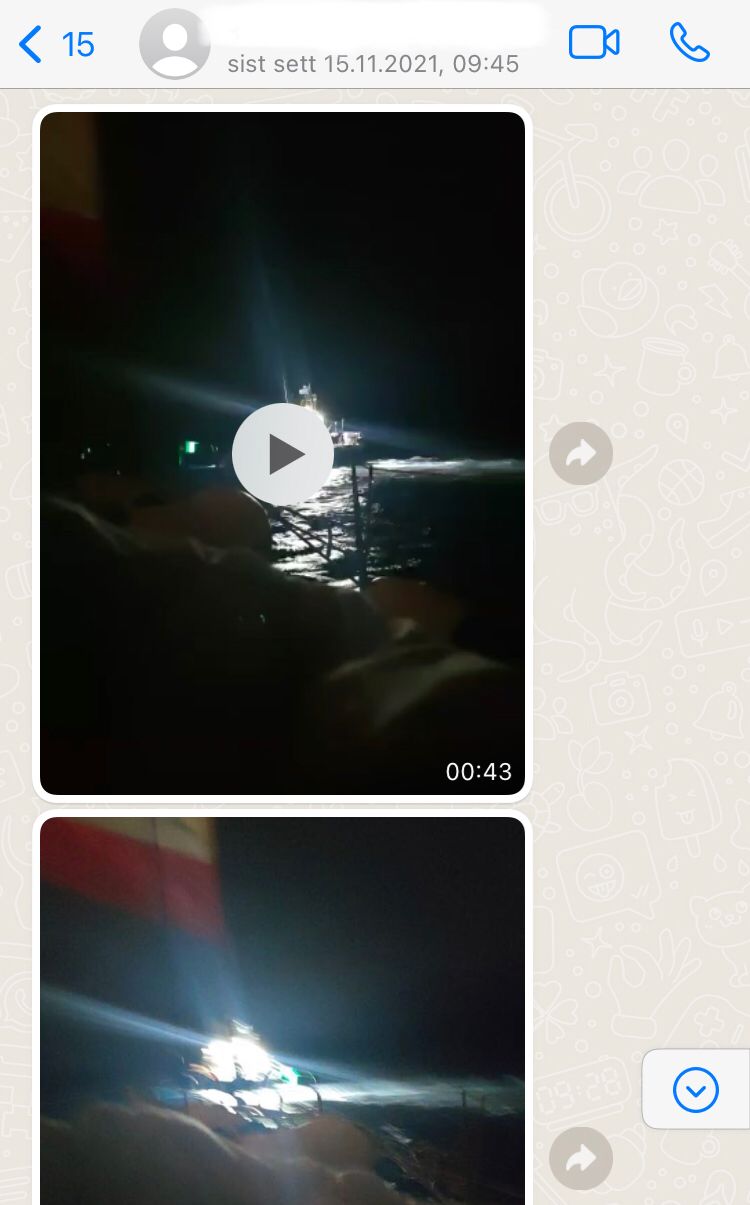

In this case they actually responded. At 01.40am, people onboard the sailboat told Aegean Boat Report that rescue had arrived, and sent several videos of a Lambro 57 coastal patrol boat with search lights in front of them, belonging to the port police in Kalamáta.

Normally, Aegean Boat Report doesn’t intervene in this sort of situation. But because of the dramatic situation and the imminent threat the boat might crash into the nearby cliffs, I made a call to assist, to try to get this sailboat to a safer location to avoid unnecessary loss of life.

The boat was dangerously close to the rocky peninsula at the sheltered bay of Mezapos north from the Cape Cavo Grosso of Mani, at one point only fifty meters from the cliffs.

The wind and waves coming from the west pushed the boat towards the peninsula, and the people onboard were panicking.

In the dark, without lights, it’s very difficult to navigate these waters, even for a skilled sailor. To get people who had never been on a sailboat before, with poor English skills, listening to instructions over the phone, to guide the boat to safety, seemed like an impossible undertaking.

Perhaps we had help from above, that someone took pity on these desperate souls, who knows, but they managed to clear the cape, and move the sailboat into the sheltered bay of Mezapos and set anchor.

Here, they waited to be rescued: to take the sailboat towards land was too dangerous, underwater rocky outcrops in the area could have capsized the boat.

For one hour people onboard waited for rescue, sent out from Kalamáta, 33 nautical miles away.

For a Lambro 57, this journey would take 45 minutes under perfect conditions and at max speed of 50 knots. In this specific case I believe that the Hellenic coast guard actually did their job, getting to location as fast as they could. But what followed is unfortunately a different story.

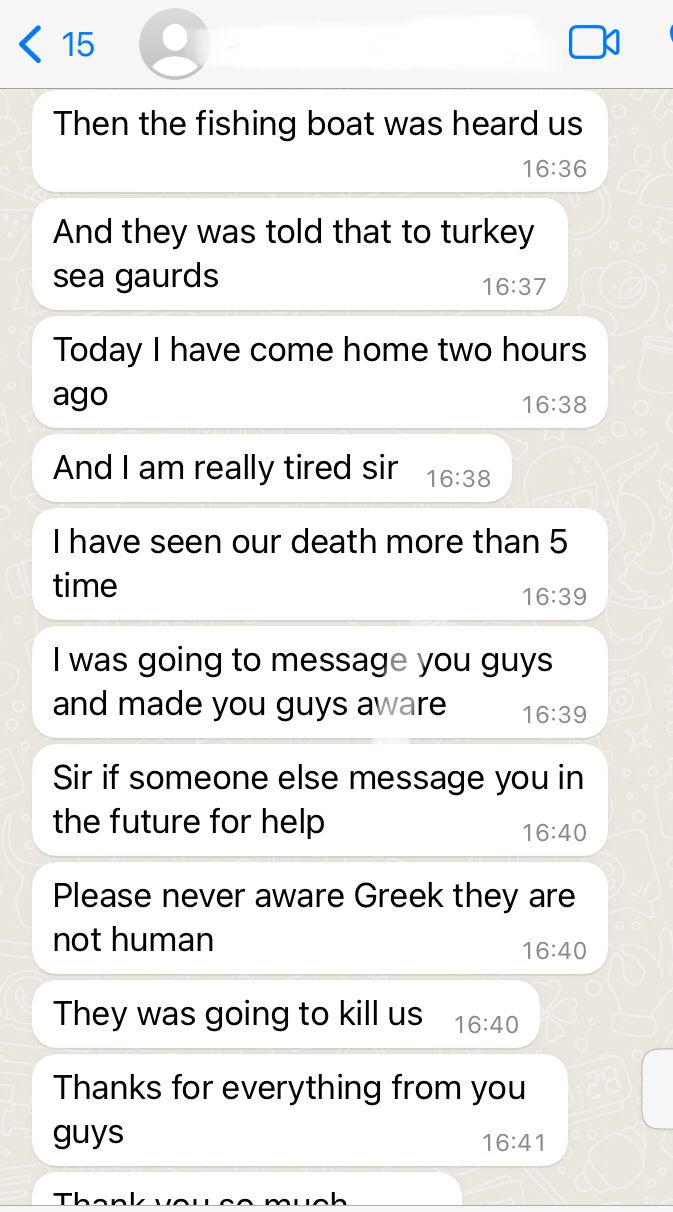

The Hellenic coast guard did not transfer the people onto their vessel. Instead, at 3am, they started towing the sailboat towards Kalamáta.

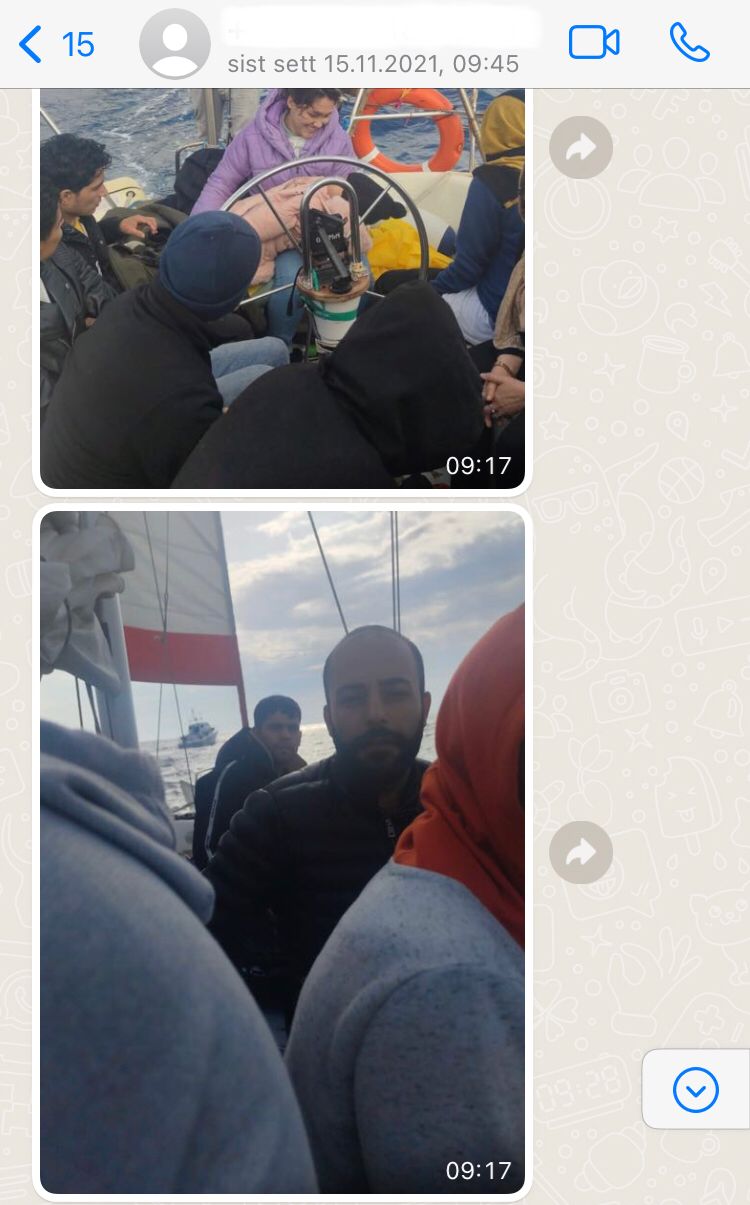

The weather wasn’t good, and the people on the sailboat were given no information about what was happening. They were scared of what would happen to them.

For the next six hours, two vessels from HCG towed the sailboat towards Kalamáta.

Aegean Boat Report had contact with the group throughout the night.

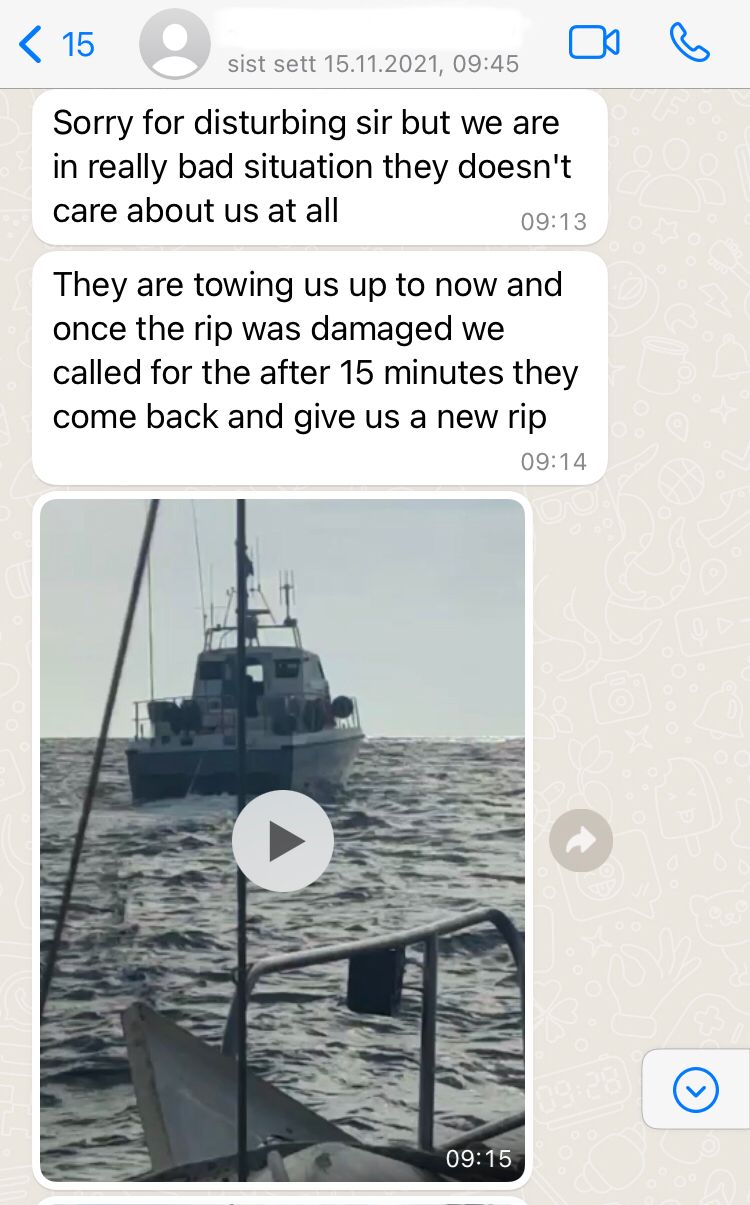

Several times while they were being towed, the rope used was destroyed, but at 9am they arrived in the Gulf of Kalamáta.

The people onboard had still not received any information from HCG on what would happen to them.

At 10.45 am, on 15 November, the people on the boat told Aegean Boat Report that a larger Greek coast guard vessel had arrived alongside them. Soon after, all contact with the group was lost, and the number used has been offline since.

That we lost contact with the people onboard the sailboat could just be them running out of power on their phones after a long night, but we found it worrying that this happened at the same time as a vessel from the Hellenic coast guard arrived alongside the boat.

We took comfort in the fact that HCG had responded to the emergency call rather quickly, and that they had towed the sailboat for six hours, 33 nautical miles, from Mezapos to Kalamáta, seemingly towards a port of safety.

Several days passed, and we weren’t able to reconnect with the group, which seemed suspicious because normally if people are taken to a camp, they recharge their phones.

There was also no information suggesting that people had been taken into Kalamáta, an area in which this kind of activity would usually make some headlines.

On Wednesday morning, 17 November, we made some inquiries, first to HCG headquarters in Piraeus, then port police in Kalamáta. Strangely, both said the same thing: they had no information on record of an incident outside Mezapos, and HCG had towed no boat to Kalamáta on the day in question, or the following days.

This confirmed our suspicion. People from this boat had been pushed back.

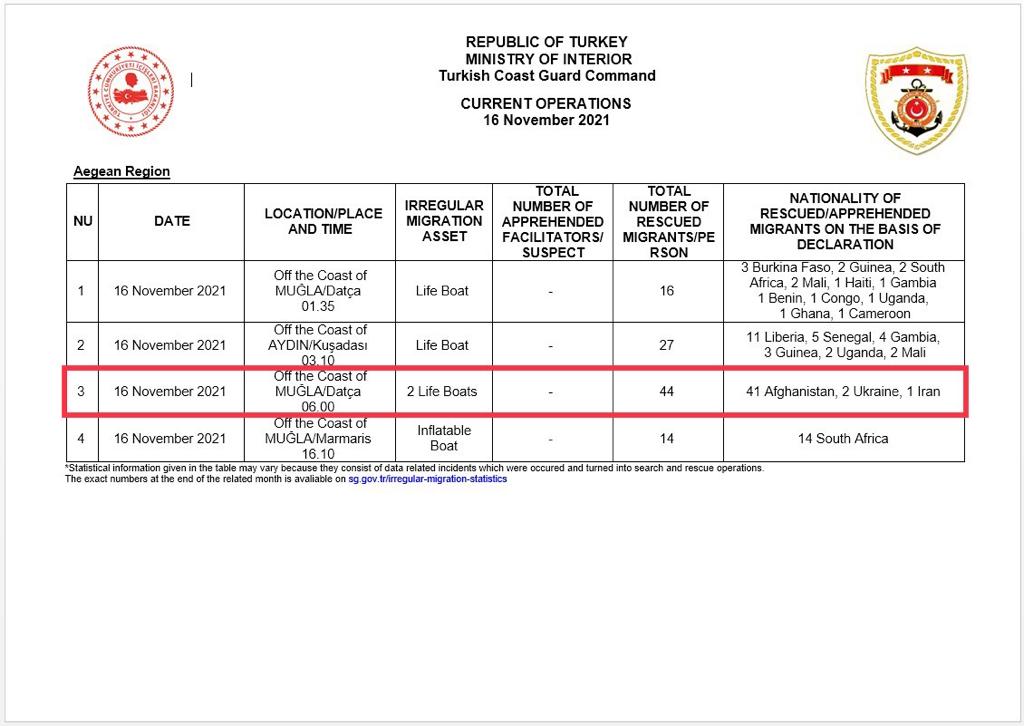

On 16 November, the Turkish coast guard published a case about 44 people found drifting in two life rafts outside Datcha, Turkey.

The photos the Turkish coastguard published were of too low quality to be useful, and a request was sent to see if they could provide additional footage.

It was actually difficult to believe that anyone would go to such lengths to push people back, to transport people across the Aegean Sea, over 600km, but we continued searching for them, in hope that we could figure out what really happened.

On 19 November, a number previously active on Whatsapp from the sailboat outside Kalamáta came online again.

We could finally get information about what really happened to this group, and what this man told us was just horrific.

In the morning of 15 November, a vessel from the Hellenic coast guard arrived and pulled up alongside the sailboat outside Kalamáta.

On the HCG vessel’s deck was a large group of armed masked men, in commando-like outfits with no officer numbers or other markings. They shouted that everyone had to come out of the boat, keep their hands up and be quiet.

They started transferring people from the sailboat at gunpoint, one by one, frisking everyone, removing their bags, taking papers, phones and money. Everything they found was confiscated.

This was done by force, shouting, hitting people who didn’t follow their instructions, even those who did everything they asked were beaten, including women and children. Nobody was spared. “They were taking special interest in the women, ripping up their clothes in front of everyone”, the man said. ‘It was just a nightmare. I thought they were going to kill us.’

After everyone was onboard the coast guard ship, a 12 hour-long nightmare started.

People were abused, men and women were randomly removed from the group, beaten and brought back. The “commandos” had them guarded at all times, at gunpoint, and no-one was allowed to speak, or even look up.

No food or water was provided, even for the children. Everything was done to make this as hard as humanly possible for these people.

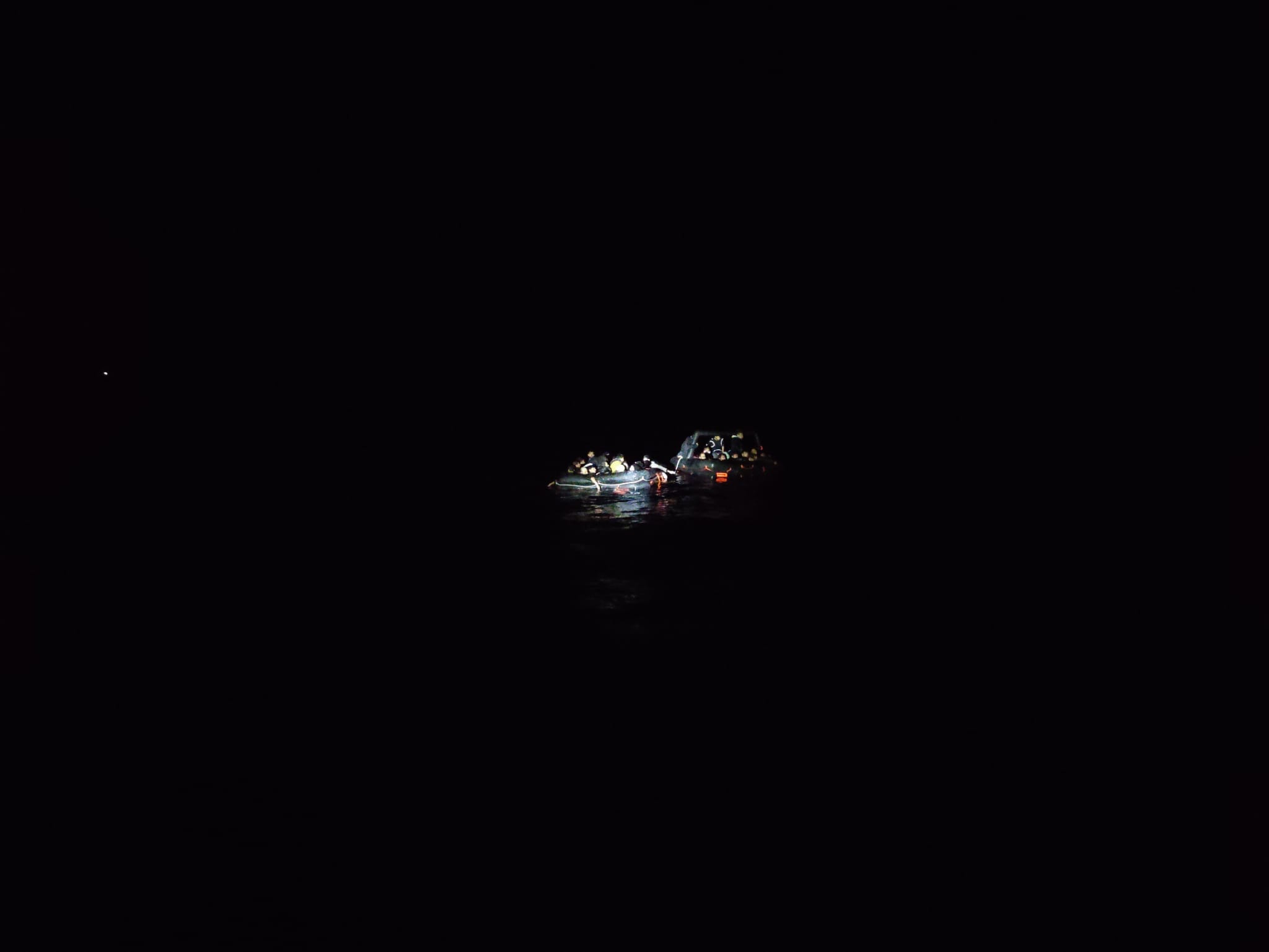

After more than 12 hours onboard the coast guard vessel everyone was forced into two life rafts. Those who refused were beaten and kicked. This is inhuman treatment by any standard, but they are only following orders, right? Why not enjoy it while doing so?

The idea is probably that if they treat them inhumanly enough, this will scare off others, and fewer people will try to cross the borders into Greece.

After hours drifting helplessly in the Aegean Sea in two life rafts, they were spotted by a Turkish fishing boat, and the Turkish coast guard was alerted.

At 6am 44 people, 41 Afghans, 2 Ukranians and 1 Iranian were found on the water outside Datcha, Turkey.

The people onboard the life rafts had no way to alert rescue services themselves, as all their phones had been confiscated by the Hellenic coast guard.

From pictures and videos provided from the people onboard the sailboat, there is absolutely no doubt that it was the same people who was found and picked up from two life rafts outside Datcha.

The problem is, we keep writing about incidents like this. And we will continue to do so until they stop happening.

We note that the law is extraordinarily-clear: every man, woman and child on Earth is absolutely entitled to travel to anywhere they want to, with or without paperwork, in order to apply for asylum.

The country that they reach must allow them to enter, and must treat their asylum applications with seriousness and care – even if they choose in the end to deny them the right to remain.

But cases like this go way beyond conversations about international law – however simple and clear those laws might be.

Because what the Greek government is doing – with the full backing on the European Union – is using its coastguard, which is supposed to rescue and protect people, instead to beat them, steal their possessions, humiliate and abuse them, before setting them adrift on the open sea.

You do not need to be an expert on international – or any other kind of – law to know that this is illegal, or indeed that it is wrong.

We are living through a period in which in the EU’s south-easternmost corner, a life-saving service has been replaced with uniformed thugs. An emergency response operation has become a militia.

Should the human race survive long enough, people will look back at this and ask: ‘How?’ How could the wealthiest political unit ever to have existed have sunk to such depths that it would allow one of its member states to savage vulnerable men, women and children in this way?

How was a government allowed to pervert a life-saving service and turn it into a violent sea militia?

And how did people stand by and let it happen?

Because that is what is happening. It is happening now, on our ‘watch’. And we will be correctly judged as inhuman if we keep sitting back and letting it continue.